Dan Harper posted this morning on MLK and Royce – Josiah Royce being the inspiration of King’s idea of “beloved community”. I decided to post my thoughts here, as part of the return to blogging which Dan among others (Scott Wells) has promoted. I’ll also be posting Dan’s post and this one on Mastodon (https://mastodon.sdf.org/@ldeg) and of course posting this link as a comment on Dan’s post.

Last year, following a discussion I wish I could recall, but possibly from the timing of my search history and downloads, sparked by a post on the Article II Commission. I’m glad to see Dan bring up Royce and remind me.

I don’t think Royce was thinking of the Beloved Community as an institution, but as what we now phrase as “world community with peace, liberty, and justice for all”. See the Great Community Chapter in this collection of his last writings.

Josiah Royce – Hope of the Great Community

I think MLK didn’t see the Beloved Community as UUA seems to be using it, as congregations or a denomination which is just, inclusive, welcoming. I think he meant something much closer to Royce’s vision of a global community which included all nations, religions, and races (which he says explicitly) and other groupings (implied), each of which is a unit of its own, but also a part of the whole, different and distinct, but with one overarching goal – living to benefit all “mankind” as he put it, where individual actions and group policies were decided not on what was best for individuals, but what was best for the world as a whole.

“That is why mere philanthropy, merely seeking for the greatest happiness for the greatest number, merely endeavoring to alleviate the pains of individual men or of collections of men, will never bring about the end for which mankind has always been seeking, and for the sake of which our individual life is worth living” (p.44)

He mentions early the body of Christ metaphor, but didn’t elaborate, but what comes to me is that the body is various, and the various nations, races, religions, and the local communities which constitute them are not homogenous, but necessarily different – the liver has a different composition, function, and structure than the lungs.

One of my concerns with the 8th Principle movement, which focuses on one group, but the spirit of which is applied to many others, is that it is still power politics, focused on securing power for individuals and groups which are relatively powerless, rather than on as Royce says, reworking systems.

Royce’s essay doesn’t really have a concise quote, but this gives some of the flavor

“In case of human individuals, the sort of individualism which is opposed to the spirit of loyalty, is what I have already called the individualism of the detached individual, the individualism of the man who belongs to no community which he loves and to which he can devote himself with all his heart, and his soul, and his mind, and his strength. In so far as liberty and democracy, and independence of soul, mean that sort of individualism, they never have saved men and never can save men. For mere detachment, mere self-will, can never be satisfied with itself, can never win its goal. What saves us on any level of human social life is union.”

(Hope of the Great Community, pp. 51-52)

MLK was a socialist, and I think his vision of Beloved Community was not of a local community — “when people of diverse racial, ethnic, educational, class, gender, abilities, sexual orientation backgrounds/identities come together in an interdependent relationship of love, mutual respect, and care that seeks to realize justice within the community and in the broader world” as the 8th Principle Project puts it, but of union, solidarity, and a global community made up of local (today we might say hyperlocal) communities that might well be homogenous within themselves, like a liver or a lung, in order to play their particular part, but all working with the goal of sustaining the whole diverse body. This post by Carl Gregg has a good bit more about King’s vision particularly.

Here is Ferdinand’s signature from Otto’s birth certificate.

Here is Ferdinand’s signature from Otto’s birth certificate.

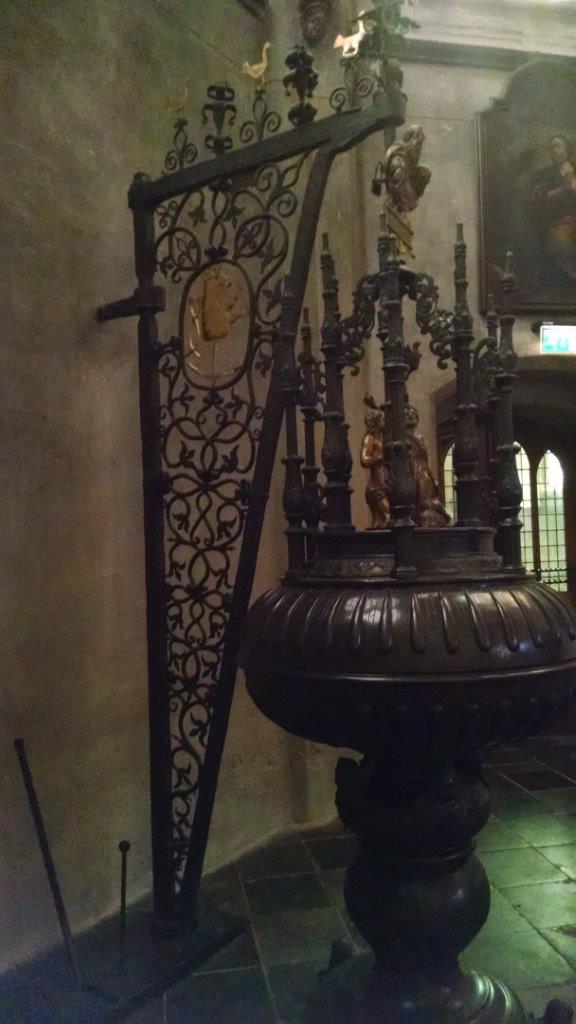

It seems likely to me that, like most churches of the time, the rich were buried in the church, the gravestones forming the floor, and they were all removed or covered, as the Bishop’s was, in the 1830s. Arnold Schoncken’s 1735 death record in the church book says he was buried in the “moederkerk”, when most other death records from the church say “kerkhof”, which is churchyard. I lit a candle for them all.

It seems likely to me that, like most churches of the time, the rich were buried in the church, the gravestones forming the floor, and they were all removed or covered, as the Bishop’s was, in the 1830s. Arnold Schoncken’s 1735 death record in the church book says he was buried in the “moederkerk”, when most other death records from the church say “kerkhof”, which is churchyard. I lit a candle for them all.

.

.